Falcons Down Under

An analysis of the Nigeria Women's National Team through the Group Stage of the 2023 World Cup in Australia/New Zealand

Come Monday August 7, Nigeria will play only their third-ever World Cup knockout match, with reigning European champions England in the opposing corner.

There can be gainsaying how daunting a task that is: not only are the Lionesses 36 places ahead in the current FIFA World Rankings, but they brought the curtain down on their three-win, nine-point Group D campaign with a 6-1 shellacking of China on Tuesday. There will be nowhere to hide come the Round of 16.

This is as good a time as any, then, to take stock of what has gone before from a Super Falcons perspective.

First, the positives, such as they are. In progressing from Group B, Nigeria kept two clean sheets and went unbeaten through their first three matches, both firsts for the nine-time African champions. This suggests a disciplined, low-risk outlook, a reality the statistics bear out: so far, Nigeria have not made a single error leading to a shot for the opponent, and are bottom three for short passes attempted. When faced with sides that boast qualitative advantages to carve you up anyway, the first point of duty is to not give them a helping hand with the trussing.

In the entire competition, the Super Falcons also rank fourth for blocked shots, have the fourth-lowest start distance, have pressed the fourth-fewest possession sequences and are in the bottom 10 for PPDA (passes per defensive action – also a measure of pressing). Taken together, it paints a picture: Randy Waldrum’s side seeks to batten down the hatches, and the focus is on remaining compact between the lines.

So far, that has worked to a degree. Nigeria is smack in the middle when it comes to the cumulative amount of xG (3.3) they have given up, although when one considers the bulk of that figure came in one game – the 3-2 win over Australia – the picture that emerges is infinitely kinder.

No player has made more tackles at the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup than Christy Ucheibe’s 18, and only Choo Hyo-joo (KOR) has won more tackles in her defensive third than Ucheibe’s 11

Now, to the negatives. Nigeria only scored in one of their three group matches, and the quality of their shots amounted to three goals, taking into account the cumulative probability of scoring. That is the exact number they have managed, so maximum props for efficiency, but while it is far from disastrous, it is still the fifth-lowest total of any team that made it to the Round of 16.

The reason for that is not necessarily a lack of quality, but of emphasis.

A team that is set up to sit deep and that seldom indulges in short, combinative passing is, by implication, one whose primary means of manufacturing threat is the attacking transition (assuming that the aim is to win football matches, of course). However, the Super Falcons are something of an oddity, in that they have appeared to completely lack any kind of transition threat.

Nigeria have no recorded direct attacks (a measure of counterattacking based on the speed and number of passes it takes to get the ball into the final third), were only caught offside twice (a useful proxy for the penetrative runs in behind that counterattacking demands) and have relatively weak at working the ball into favourable shooting range, per their average shot distance of 18.4 yards.

To indicate there is more to this than simple variance or quirkiness, on even the rare occasions when they engaged higher up the pitch and managed to win the ball, they were poorer at turning those turnover opportunities into shots than the likes of Panama, Australia, Costa Rica, Morocco and Republic of Ireland.

Important note: all of these sides win the ball back in advanced positions less frequently than Nigeria. Even with the benefit of a shorter distance and fewer opponents to bypass, the Super Falcons simply do not transition well.

This supports the idea that there simply is no systemic focus on it (none that is evident to the viewer anyway), which is odd: how then is Waldrum hoping to score goals?

Indeed, from an attacking standpoint, a lot seems to be left up to players forming relationships between themselves.

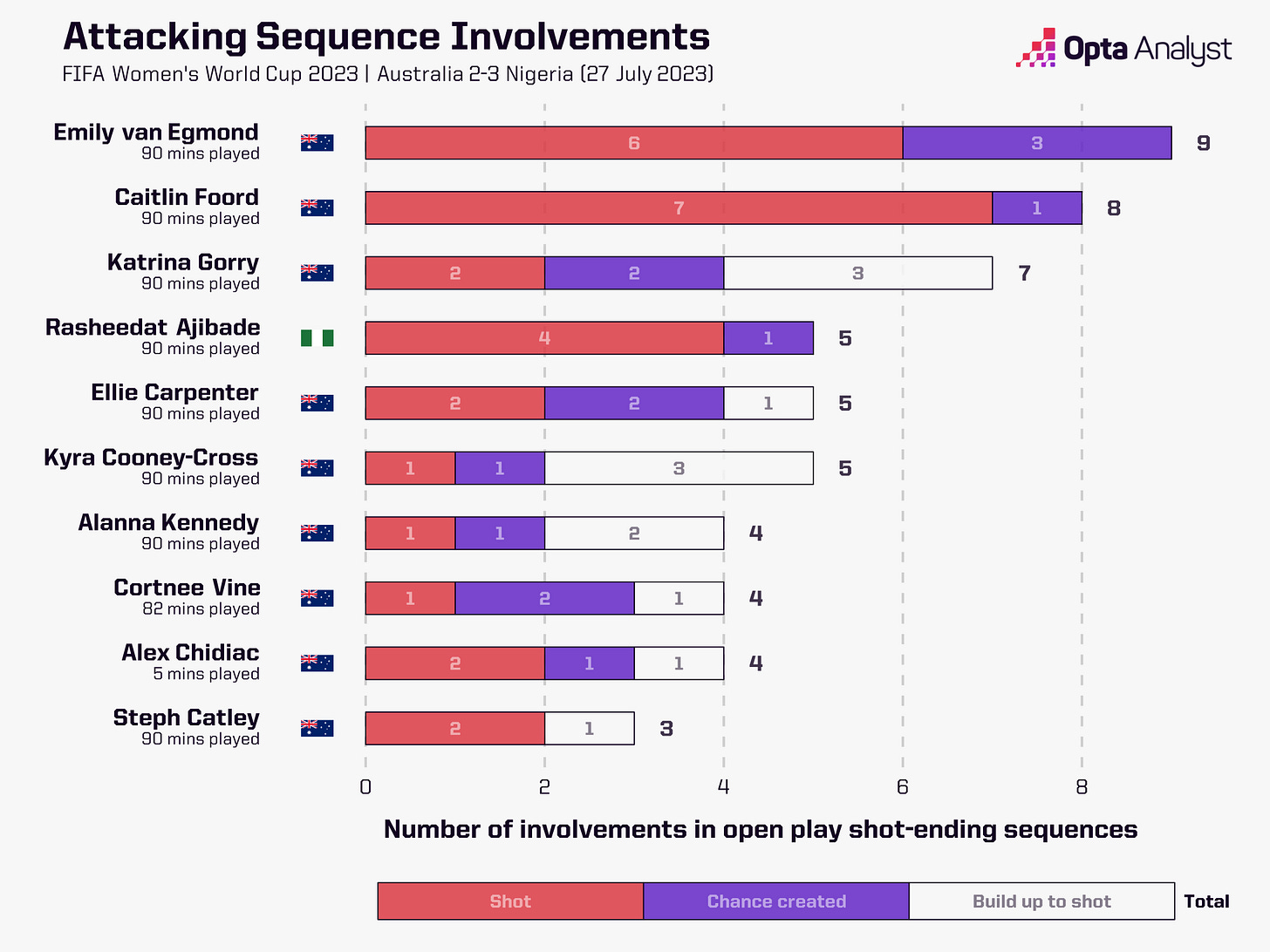

It is no shock, then, that when Nigeria have looked at their most fluent, it has been with both Toni Payne and Rasheedat Ajibade on the pitch. While the Super Falcons’ squad is overwhelmingly populated by either runners or tacklers, both are ‘small space’ players, and when they are in close proximity, Waldrum’s side looks halfway coordinated in the final third.

Of players who have completed 15+ take-ons at the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, only Giulia Dragoni (ITA), Jennifer Hermoso (ESP) and Caroline Graham Hansen (NOR) have higher success rates than Toni Payne’s 61.1%

So, what you have is a situation in which a team is set-up for the counterattack, but its most reliable creative formula involves two needle players combining with one another in established possession. Quite the paradox. It does not help either that they are essentially figuring things out on the fly, and so their understanding is not always as effective as it could be.

A further wrinkle in this regard is the composition and organisation of the team around them.

Nigeria’s shape over the course of the campaign has shifted from the 4-3-3 that started the barren draw with Canada to the 4-2-3-1 of the latter two matches against Australia and the Republic of Ireland. Part of that is to do with the fact that, in rather unfortunate circumstances, Deborah Abiodun was sent off late in the aforementioned stalemate with the Olympics champions and subsequently banned for three matches (more on the downstream effects of her continued absence later). In both cases, the most advanced role has gone to Payne, with Christy Ucheibe and, following her return from suspension, the impressive Halimatu Ayinde sitting deeper, and wide players – one a forward, the other more of a midfielder – either side.

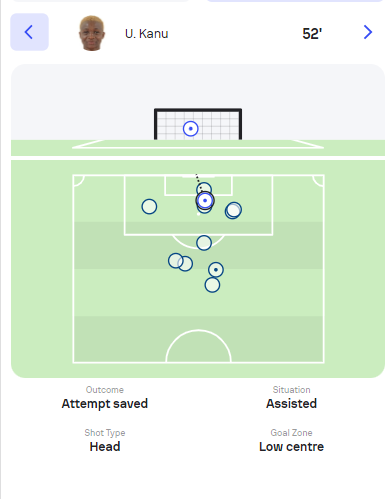

The main problem, however, is in Waldrum’s insistence on fielding his forward on the left. In the first match, it was Ifeanyi Onumonu, and in the two games since, it has been Uchenna Kanu. The Racing Louisville forward has, to an extent, justified her inclusion with her equaliser against the co-hosts and her brilliant header against Ireland. However, she is altogether the wrong profile for that side of the pitch; this is evident not only by the zones from which she has gotten her two shots so far (both right-of-centre inside the penalty area), but also in the fact that the team has almost always improved whenever she and Ajibade have switched flanks.

Kanu is not the sort of wide forward to receive the ball to feet, dribble in-field and shoot. Rather, she thrives on an economy of touches, and is at her best taking up scoring positions and finishing instinctively. Being right-footed, the angles on the left simply do not suit her, and even if they did, she would require a different profile of full-back to Ashleigh Plumptre to make it work.

In attacking the box, Kanu essentially leaves Plumptre alone to carry the flank, a suboptimal state of affairs especially as we have established that Payne tends to drift to whatever zone Ajibade is in. As such, when the ball gets to Plumptre’s feet, the move either gets reset or dies; being a centre-back, she cannot carry the entire left side alone with no one to combine with.

What’s worse: Ajibade is not quite the correct profile to dovetail with Plumptre either. (The complementary left-back, in this respect, would be a more aggressive overlapping presence, in the mould of Rofiat Imuran, who has yet to taste a minute of action in Australia.) Regardless, there is a benefit to fielding Ajibade on the left, and this is that, being right-footed and more of a midfielder than a forward, she is able to receive the ball on the half-turn, angle her body toward the centre and immediately have a full view of the pitch.

This facilitates her combinations and aids ball retention; Nigeria’s best spells in possession have come with Ajibade working from the left and coming into the middle third. And even in the final third, she is a much better ball-carrier than Kanu, able to front up the opposing centre-back and dribble on either side, before crossing or shooting.

There is a further reason to have Ajibade on the left instead, and that is to do with Asisat Oshoala, the de facto star of the team.

To address the elephant in the room: yes, there is a marked difference in production between the version of Oshoala that scores by the bucketload for Barcelona and that which turns out for Nigeria. Also yes, it can sometimes seem like the team is actually more fluent and dynamic in her absence. As with most such cases though, the problem has nothing to do with the player’s commitment or desire, however vigorously the idea is propagated and believed.

As a means of understanding the issue, close your eyes and think of the last time Asisat Oshoala had a truly great tournament for Nigeria. A player of that quality is bound to have moments of eruption, but a consistent series of performances? You would have to go back to the 2016 Women’s Africa Cup of Nations, to a time when she still typically started from a wide position and played a freer role; this is, after all, a player whose calling card from a young age was her versatility.

For all of her range, however, she has never been good at receiving the ball with her back to goal. And while, in her club career, she has been buttoned down, her game domesticated to the centre, Nigeria’s coaches have cribbed the answers but none of the workings.

Used as a more conventional striker (i.e. required to fulfil all of the functions therein) at Liverpool and Arsenal earlier on, Oshoala struggled for consistency and impact. However, at Barcelona, where a surfeit of technicians means she is essentially removed from the build-up and allowed to hone in on runs into depth, the 28-year-old has positively exploded.

That then is the complete template: a midfield zone with enough quality ball-handlers to permit Oshoala to focus exclusively on pulling defences out of shape. This could happen in the form of reverse movements with the wide forward (as was the case in the first half of the opening group match against Canada, when she and Ifeoma Onumonu dovetailed to good effect) or by actual runs in behind to stretch the pitch vertically.

It is in these situations that she manifests the most threat; witness, for instance, the sheer panic she caused following simple balls over the top for her big chance against Canada and her goal against Australia.

Why is that not happening (enough) then? For one thing, as previously mentioned, Ajibade fielded on the right hardly helps. Not only does that affect her receiving angles and her ability to combine centrally, but she tends to hold the width more on that flank and play a more vertical role that simply does not suit her. However, the other problem is the continued absence of Deborah Abiodun.

Her superb performance against Canada on opening day saw Abiodun nicknamed ‘Kante’, and while that all-action display certainly bore some resemblance to those of the France international, there is a lot more to her game than tenacity and work ethic. She can play a bit too—in fact, she is more of a creative player than she is a destructive one.

That level of comfort in possession, especially in advanced areas, made a 4-3-3 shape viable, thereby increasing the Super Falcons’ presence between the lines of the opposing midfield and defence. In her absence and following the return of Halimatu Ayinde, the shape of the team has been altered to more of a 4-2-3-1, albeit with Christy Ucheibe now having a bit of licence to break out of the double pivot from time to time, especially off the ball.

Now, Ucheibe has her strengths, but she is much less comfortable playing ahead of the ball and receiving in advanced areas. As such, if Ajibade does not switch flanks and come into more narrow positions, there is no one for Payne to combine with between the lines centrally unless Oshoala drops deep to receive with her back to goal.

Therein lies the problem, the hole in the donut, the crux of Nigeria’s lack of attacking fluency.

Onto England on Monday.

The good news is that the Super Falcons have already played two sides ranked inside the world’s top 10 and emerged unscathed. Waldrum’s side have also kept two clean sheets as previously mentioned, and actually have a positive head-to-head record against the Lionesses.

The not-so-good news is that, unlike Canada and Australia, who came into the tournament in poor scoring form and were missing their best striker respectively (heck, even Ireland were far from incisive: their own goal in the tournament came direct from a corner), England actually have the means to punish even the minutest of lapses.

It is also difficult to tell quite how Sarina Wiegman’s side will line up. Having previously displayed vulnerability to transitional attacks, especially in the victory over Denmark, the Dutch manager altered her side’s shape against China, going to a 3-4-1-2 and beefing up the middle, partly as a response to the absence of the influential Keira Walsh. Considering Nigeria’s theoretical threat of pace in behind, it seems fair to assume she will stick to that on Monday; either way, the counter-attack is the clearest route to success against this England team.

It is a shame then that, to this point, Nigeria have yet to display any great proficiency on the break, despite having the tools to threaten in that exact scenario. It is one thing to sit deep against opponents that lack the chops to hurt you, as you can simply make the game a non-event and hope for kind bounces (a deflected shot falling to your forward inside the box, or an opposing defender heading the ball into your path with the net gaping) or broken sequences (the second phase of a corner kick).

However, faced with a team like England who know where the goal is, you are a sitting duck without a proper plan to counterpunch, as well as the timing and accuracy to execute. The inevitable will feel like mercy when it does arrive.

If the Super Falcons are to pull off the improbable, here are a few basic points of duty.

Constant bead on Lauren James: While Georgia Stanway is able to advance, in this 3-4-1-2 England are basically playing two midfielders behind the ball, sacrificing control in possession for defensive solidity. James is the one player consistently between the lines, and since she will more often than not skew left with her movement, the job of keeping tabs on her will likely fall to Ucheibe. The Benfica midfielder can man-mark James, safe in the knowledge that Ayinde is minding the shop in front of the defence.

Outlets: Against a back three, it is important to run the channel, so it would be a good idea to have Oshoala peel off to the left and test Jess Carter for speed. However, she cannot be the only one; Kanu should be up there on the opposing flank to exploit the space behind Rachel Daly, make blindside runs and offer incision. Which leads to the next point…

Ajibade left from the off: Not only is this important for the reasons explained in this piece, but it is important that one, not both, of Nigeria’s wingers track a wing-back. Ajibade going with Lucy Bronze in order to allow Kanu to remain in a more advanced position on the right is a fair compromise, with Michelle Alozie pushing up to engage Daly. That leaves the Super Falcons with 3v2 at the back, handy as Lauren Hemp, usually a winger, started right of centre against China and is the one of the front two who will more readily threaten in behind. Plumptre can sit narrower to engage her, or even jump forward to meet Stanway with Ayinde covering the gap and Blessing Demehin being the spare man.

Bring the Payne: Her ball-carrying and ability to ride contact means she will need to have a stormer if Nigeria are to eke out a result here. Unfortunately for her, more than half that job will involve running off the ball in search of pockets in which she can receive the ball with time to get her head up. No mean feat up against a double pivot, but if she can work on the outsides of Stanway and Katie Zelem, there could be a chink to exploit.

Dead balls: Self-explanatory, this one. They might as well be death balls if the Super Falcons cannot defend them properly. Especially corner kicks.

My comment on the article

Great piece Solace. I am pained that Waldrum has not taught this team how to attack, the same way he taught them how to defend as a low block . I pray for the best, but I don't see how we can beat England. I tipped them to win the tournament and it is looking very likely