Nigeria's footballing identity

On Friday, November 19, 2021, Oscar Washington Tabarez was sacked as manager of the Uruguay national team after more than 15 years.

He had, to that point, been in the post for over 200 games – if you take into account his previous two-year spell in the late 1980s – winning one Copa America in 2011. If that seems like a rather sparse honours sheet, it is because of modern football’s obsession with the concept of the “serial winner”, where ultimate worth is determined by titles collected like infinity stones and used to snap all criticism and dissent into oblivion. It is also partly my fault: to understand what exactly Tabarez represented, the sheer size of his footprint on Uruguayan football, is to realise that not even the term “manager” did him justice.

By instituting the ‘Proceso’--an all-encompassing framework for the revolution of the country’s football--the former primary school teacher completely altered the course of football in Uruguay, co-opting the ‘garra charrua’ ideology from its brutish origins into something positive and aspirational. “We came up with a project to institutionalise the entire organisation of Uruguayan football and the training of all football players,” he explained. He was not only the coach of the senior national side but the overseer of all its teams at all levels; more accurately the technical director.

His framework was not necessarily of a tactical nature, more a cultural one. In terms of style, Tabarez fell on the catch-as-catch-can side of things, as happy springing forward on the counter as taking the initiative himself, and flitted between different systems, sometimes even within the same match. What he wanted to do, and what he did, was to win hearts and minds; in doing this, he also won matches. Lots of them.

Over the course of the past three weeks, the job security of interim Super Eagles coach Austin Eguavoen swung from ironclad to non-existent to complicated.

With the World Cup qualifying playoff on the horizon, naturally, the discussion has already progressed to what the reconstitution of the coaching crew means and how it might play out in practice. While I have a few broad ideas, I feel like this critical juncture is a good fork in the road to have a think about what exactly Nigerian football even is about.

This is particularly relevant because the biggest criticism of former coach Gernot Rohr has revolved around playing style. Broadly speaking, the 68-year-old won the matches he had to, qualifying Nigeria for every international tournament going in his time in charge (a fact he has been only too happy to remind everyone of through his media proxies), and he at least made a respectable fist of competing at the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations (the less said about the 2018 World Cup, the better). In spite of these, the opinion of him up until the point of sacking was mixed to negative.

It is not because, as some like to imagine--and some say outright--Nigerians are incapable of recognizing a good thing when they see it. It is because the reception of even an objectively good thing can depend on the manner in which it is given or achieved.

To use qualification as a wand to ward off criticism rang a little contradictory when the very reason Rohr was appointed was precisely that failing to qualify for the 2015 and 2017 editions of the AFCON was considered an underperformance. In other words, those two outcomes were viewed as anomalous in light of Nigeria’s standing and available quality, not a confirmation of minnow status.

This is a slight tangent, but it is an important one in understanding why Rohr got short shrift from many, and also in explaining why it was never going to be enough to simply return Nigeria to the position of serial tournament qualifiers.

However, where the criticism of the German fell down a bit was in its lack of clarity. If the desire was to dominate opponents and score lots of goals, in what way was that aim to be pursued? If it was to entertain while keeping a winning ethos, by what framework could that be achieved? If it was to “play good football”, what does this mean within the context of Nigerian football?

So what was the ideal of Nigerian football that Rohr was supposed to reach for, but failed to? In a 2011 Daily Trust column, former Nigeria international Segun Odegbami attempted to put it into words.

“Power, speed and athleticism come naturally to the Nigerian,” he wrote, “and, when properly channelled and laced with some level of skill and organisation, [it] could become a lethal combination. Nigerian players are athletes first before being artists. To get the best out of them requires maximally applying their natural gifts in strength, speed and athleticism.

“Through the generations, Nigerian football evolved a style that became our football culture—that of using our natural gifts and playing effectively down the wings, the only area of the football field where there is the space to do so.

“It was a simple formula that worked and worked and worked: the Nigerian team is defending its goal. It takes possession of the ball, sends a long telegraphic pass from defence or midfield to either of the wingers racing to get behind opposing defenders. The ball is chased down by fast Nigerian wingers running at and past opposing defenders and sending lovely crosses to waiting attackers to be buried behind the goalkeeper!

In the years between 1976 and 1996, Nigeria established a football culture of some sort using this simple but very effective style of play.”

While this is a succinct distillation of what Nigerian football was at its peak, Nigeria’s campaign at AFCON laid bare some obvious issues.

Nothing “simple” remains “effective” in perpetuity. Leave something in its most basic form long enough, and sure enough, its potency will begin to wane.

Just ask Eguavoen, who found that out to his detriment against Tunisia in Garoua.

The basic premise of playing in this fashion – that there is space to be enjoyed on the flanks – is also basic conceptually and in understanding. While there is relatively more space in wide areas, for most good defending teams the function of that space is as a trap and/or a pressing trigger, as the presence of the touchline limits the receiver’s field of movement, as well as his passing options.

This was precisely the mechanism by which Eguavoen’s hippie, free-loving ideology was cruelly exposed and exploited by the Carthage Eagles in Garoua.

That is not to say, of course, that the idea of concentrating build-up in wide areas is inherently wrong or unworkable. However, there must be some degree of sophistication to the scheme in order to bring it into the modern day.

Senegal, who won the AFCON, were almost entirely based around their play on the flanks, necessarily so considering their lack of a creative midfield player. Their system, however, was not about hitting their wingers in space with booming diagonal passes, “telegraphic” or otherwise, and requiring them to outsprint the opposing full-back. Instead, it was concerned with creating overloads, occupying space intelligently and working quick combinations to either open up that flank or expose the opposite side of the pitch for a quick switch.

Clearly then, it was not so much that what Odegbami – and Eguavoen – had in mind was wrong, but that it was simply too basic. It was a skeleton, in more ways than one: part a relic of the past, part a support structure on which something would have to be built in order to attain viability.

There are a number of separate questions that arise from this, of course.

Do the socio-cultural truths that formed the basis of Odegbami’s understanding of the necessity of wing play still hold true? For instance, is it (still) fair to say that Nigerians are “athletes first”? And, if it is, is it a potent enough truth that it should inform what our footballing ideal is? If it is not, where on the athlete-artist spectrum do we fall?

Are there other social mores and habits that can enrich or even significantly alter the framework? (As an example, it has always struck me as strange that, given the Nigerian penchant for shortcuts, there is not a stronger emphasis on the use of set-pieces.)

Can we leverage the diversity within the country – in terms of population, culture and topography – in creative ways when it comes to player development? For instance, tight spaces tend to produce playmakers, and so it should come as no surprise that a lot of Nigeria’s most creative players have come from its more densely-populated South; by contrast, wingers are likelier to spawn from the North. These are broad generalizations, of course, but you get the point.

All of these considerations are germane for the simple reason that, in figuring them out, we may finally be able to synthesize a unifying document for the training and development of Nigerian footballers and coaches.

The evolution Odegbami outlined was achieved, by his own estimation, in 1976. That was a significant year in Nigeria’s football, as the national team achieved their first-ever medal finish at the Africa Cup of Nations in Ethiopia.

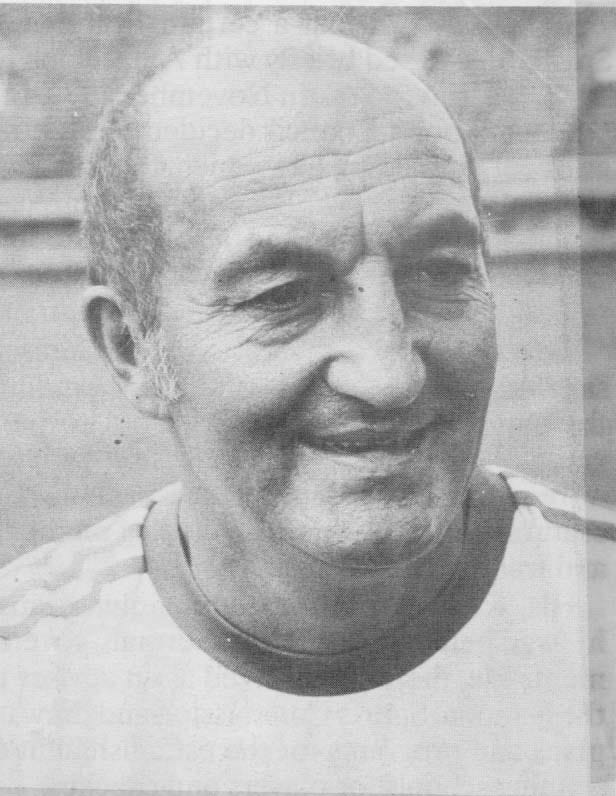

The coach at the time was Tihomir ‘Father Tiko’ Jelisavcic, a Serb who, while espousing an attacking style, was utilitarian above all else, preached physical preparation and was a believer in “an easy and effective game model” with quick attacks and lots of running, according to those he trained while working in Mexico.

How much of what Odegbami described was simply Father Tiko’s catechism?

Nigerians as a people are, historically, captives to their own success, and will often come to consider the manner of it to be prescriptive. Is it beyond the realm of possibility that what ‘Mathematical’ considers intuitive and natural is actually a learned, internalised understanding, based on what Jelisavcic dictated?

It surely is not inconceivable, but by the same token, it is impossible to tell for sure: Father Tiko passed away in 1986, and so seeking his view on the matter is simply out of the question. However, what is obvious is that a new reckoning is needed, a modern referendum of sorts, after which Nigerian football can finally emerge with a plan and framework, not just for negotiating World Cup qualifying cycles, but for its holistic development at all levels.

More than a coach, indigenous or foreign, abrasive or avuncular, Nigeria needs its own ‘Proceso’.