Nigeria's GOATs: 4-1

Following the publications of Parts 1 & 2, the top four pretty much picks itself. The intrigue, however, is in how they place. So, once again, if you have not read the previous parts in this series, please do so.

This covered the methodology and revealed 10-9…

… and this revealed 8-5

Now, without further delay, here is the top four.

4. Segun Odegbami

Active years: 1970-1984

Honours: Nigeria Professional Football League x3, Federation Cup x3, African Cup Winners’ Cup x1, Africa Cup of Nations x1

Ability: 10

Club career: 4

International career: 1.75 (multiplier: 0.5)

Social impact: 5

Leadership: 3.5

Total: 24.25

Veteran Nigerian journalist and historian Calvin Onwuka refers to Segun Odegbami as “Nigeria’s first national football star”, a fitting epithet to encapsulate not just how good of a footballer he was, but also the reverence in which he was held.

It is no exaggeration to state that people came from far and wide to catch a glimpse of Odegbami in his pomp, or that every football-loving child growing up in that era wrote the number 7 on the backs of their shirts in tribute. The great Ebenezer Obey celebrated him in song without ever having met him. By his own admission, he was not passionate about football, but even that made his wizardry seem effortless and only caused the sport – and its fans – to adore him more.

Positionally, it is rather difficult to even pin Odegbami down. Capable of playing all across the front line, ‘Mathematical’ was very modern in that sense, and he stood out not just for his considerable ability, but also for his looks and his erudition. However, it is with the right flank that he is most frequently associated, and it is thence that he frequently gave lessons to opposing full-backs.

Not only was Odegbami rapid, but he had a loose dribbling style that allowed him to not so much power past opponents as glide. There was end product to boot as well, as his superb ball striking off both feet – in service of both precise flighted crosses and a repertoire of finishes – combined with his movement off the flank and heading ability to form a dizzying cocktail of attacking menace.

His famous opening goal against Algeria in the 1980 Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) final, an exquisite toe poke after a swivel in a tight penalty area, demonstrated the natural feel for where the goal was that saw Odegbami average a goal every other game at international level for Nigeria, a competitive ratio in any era. Indeed, despite an international career that only spanned five years, Odegbami is the second-highest goalscorer ever for the national team, with 23 goals.

At club level, he was just as prolific and influential. With him in attack and Muda Lawal in midfield, Shooting Stars were one of the two dominant Nigerian clubs of the 1970s and early 1980s. They played second fiddle to the great Enugu Rangers side, only winning the title thrice, but the rivalry between the two teams defined the country’s football, and Odegbami’s presence was often considered the difference between success and failure.

So crucial was he that, for the 1975 Cup Final, fans of ‘Sootin’ waited outside Odegbami’s exam hall, whisking him away to the stadium through hellish traffic upon the conclusion of his polytechnic examinations. Coach Allan Hawkes, having not reckoned with his availability, insisted Shooting Stars could win without their star player. Hawkes was mistaken: they were duly defeated 1-0.

While the Flying Antelopes filled up on titles domestically, it was, ironically, Shooting Stars who would fetch Nigeria its first continental title in 1976. They came through an almighty scrap against Zamalek in the semi-final before beating Tonnerre Yaounde 4-2 on aggregate; Odegbami’s prowess in the air contributed to both victories at key moments, and in total he scored half the team’s goals en route to that success.

Amidst all of this achievement, there are some caveats that prevent him from placing higher. For one, as previously mentioned, he had a rather short international career. Also, he never succeeded in winning the CAF Champions League, reaching the final in 1984 only to be denied by Zamalek, arguably robbing him of the recognition of being named Africa’s best player.

Most pointed, however, is the fact that he failed to reach the World Cup. Odegbami cites this as one of his chief regrets, and even admits some culpability; the loss to Tunisia in 1977 is remembered for the Godwin Odiye own goal, but ‘Mathematical’ endured an uncharacteristically poor day in front of goal as well, missing two excellent chances in a game from which Nigeria needed a draw.

If one were minded to focus on what’s missing, those stick out like sore thumbs. With so much to appreciate, though, why would anyone want to do that?

3. Nwankwo Kanu

Active years: 1992-2012

Honours: Nigeria Professional Football League x1, Eredivisie x3, Premier League x2, English FA Cup x3, UEFA Champions League x1, UEFA Cup x1

Individual awards: African Footballer of the Year x2

Ability: 9

Club career: 5

International career: 3 (multiplier: 1.0)

Social impact: 5

Leadership: 3

[Extraordinary achievement: +1]

Total: 25

Pointless though the exercise may be, it is sometimes tempting to wonder what would have happened had Nwankwo Kanu not been diagnosed with the heart condition that came so close to ending his playing career in 1996.

By that point, his considerable ability had already brought him a Champions League, three league titles, the African Footballer of the Year (an award that, at the time, only two other Nigerian footballers had ever won) and a move to the biggest league in the world. That, despite the erosion of his stamina and explosiveness, he still went on to have the career he did post-op is testament to his greatness.

Even taking away the triumph at Atlanta 1996 and its significance in terms of putting the country’s football on the global map, there has been no Nigerian footballer more decorated than Kanu. That he failed to win (or even score a goal at) AFCON is the one black mark, and is a stick often used to beat him. It is a reductive criticism but, even allowing it, he still comes out extremely well for his entire body of work.

Besides, no one who actually saw him play could have any doubts as to how ludicrously talented ‘Papilo’ was. Has there been a more spatially aware player of Nigerian extraction? One with a better touch? More accomplished at playing the final pass? Better skilled at link-up, hold-up and associative play in the final third? In full flow, Kanu was a technical marvel and a hypnotist: constrained neither by space nor time, freezing defenders and making goalkeepers lie down by virtue of feints alone, capable of every trick and flick imaginable.

So what if he never scored at AFCON? From his orgasmic trio of assists in one game against Tunisia in 2000 (having received his second African Footballer of the Year award prior to kick-off), to his assist for the winner against Cameroon in 2004, to his game-saving cameo against Senegal in 2006 – there was clearly no shortage of ability or impact, simply of good fortune.

Following Champions League success at Ajax and the rigours of corrective heart surgery, Kanu recovered sufficiently to play a part in Inter’s successful 1998 UEFA Cup campaign, but it was at Arsenal that, by his own account, he played his best football.

Brought in as something of a stop gap, his ability to both lead the line and function deeper meant he played a lot of minutes, contributing to probably the most successful period of the club’s history (two league titles, two FA Cups) and turning out a number of iconic performances along the way. Almost as significantly, his arrival in North London almost single-handedly built the Gunners a fanbase in Nigeria.

He even, somehow, managed a second rebirth. At the age of 32, via a stint at West Brom that seemed to confirm his best days were behind him, Kanu rolled back the years at Portsmouth. Like Samson imbued once more with the strength of old, he not only hit double figures in the league for the first time since his first full season in English football, but led humble Pompey to their first major trophy for 58 years in front of a record crowd at the new Wembley.

Goals in the semi-final and final cemented Kanu’s place as a Portsmouth icon forever, and spoke to his enduring genius. “A lot of people always ask questions about me, but I keep coming out with the answers,” he said following that triumph over Cardiff. “That is talent. I have to work hard, but the talent is there. I didn't disappoint myself, I didn't disappoint anybody.” No, he did not.

Kanu excelled at making difficult things look easy, a fact that made his opposite penchant for making easy things look difficult easier to forgive. “Great players can prove you wrong,” former boss Arsene Wenger said following his famous hattrick at Stamford Bridge. “He is a winner, and when you are a winner you do what is efficient.” For Kanu, that meant doing the unconventional at times, even if it was the more difficult option technically, simply because it was the simplest way to achieve the goal. That, more than anything else, was what made him special.

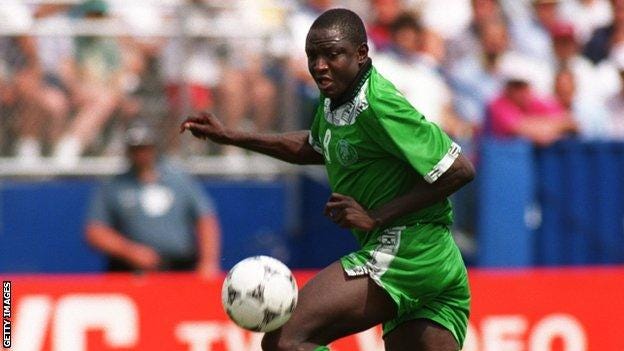

2. Rashidi Yekini

Active years: 1981-2005

Honours: Nigeria Professional Football League x1, Côte d’Ivoire Premier Division x2, Federation Cup x2, Côte d’Ivoire Cup x2, Africa Cup of Nations x1

Individual awards: African Footballer of the Year x1, Primeira Liga Golden Boot x1

Ability: 8

Club career: 3.5

International career: 5

Social impact: 5

Leadership: 3

[Extraordinary achievement: +1]

Total: 25.5

It may seem churlish, in light of all that Yekini achieved, to describe his success as being conditioned by failure. However, the failure was not his own; had coaching in Nigeria been better, there is a strong argument to be made that he could have been even greater. This is, after all, a player who peaked extremely late, in a raw state for much of his career before fully realising his potential at Vitoria Setubal in his 30th year.

Of course, even his unrefined form had not only been enough to spark bidding wars across the country, but had also seen him invited to the national team, where he would go on to write his legend in gold.

Nevertheless, it is not a slight on him to say that he was far from a technical wonder. While he improved markedly with time, Segun Odegbami’s first impressions of him upon his arrival at Shooting Stars in 1982 were of a “tall, gangly and clumsy player who was very limited at dribbling with the ball”. There was a brutal efficiency to his football, one that dealt chiefly in goals and what facilitated them: movement.

In that respect, he was, according to international teammate Sunday Oliseh “ahead of his time”. Even though his finishing was far from dead-eye, time and again, Yekini got into superb positions. In this era of Expected Goals, he would have been a darling of football analytics.

As soon as he figured out the rest, he was nigh-on unstoppable. At international level, he scored in four consecutive AFCONs, improving steadily each time (his tallies were one, three, four and then five) and winning the Golden Boot in the latter two.

His apotheosis came in the 1993-94 season, where he not only ran riot for Nigeria in Tunisia en route to a second title, but led the Portuguese topflight in goalscoring (with 21) and took lowly Vitoria to the brink of European qualification. In the 5-2 demolition of eventual champions Benfica, Yekini was rampant, scoring twice and hitting the bar; he would also score twice against Sporting, seeming to relish punishing the leading lights of the division.

Midway through the campaign, he was named African Footballer of the Year; by the end of it, fans of Vitoria has taken to calling him ‘O Deus Negro’ – the black god. (In a Biblical parallel, following a league match, he once was forced to leave the stadium naked, as frenzied fans clamoured for his garments.)

Vitoria were far from a glamorous outfit, and so titles at club level outside of a handful of successful seasons at Africa Sports were limited. However, Yekini more than made up for it by being the be-all and end-all for the national team as far as goals were concerned: in 58 appearances for the Super Eagles, he scored 37 goals. “He was the player who qualified Nigeria to our first-ever World Cup,” teammate Samson Siasia said matter-of-factly. “He was the best player Nigeria ever produced.”

His goals ran the gamut from predatory to powerful, but you could be certain that, whatever finish he plumped for, it was the most pragmatic, logical one possible in that particular scenario.

His name invariably became a byword for goalscoring in the Nigerian lexicon, as he captured the imagination not just for his goals, but also for his quiet, professional attitude toward his craft. “Rashidi’s style of play and how he banged in the goals was the drive and source of motivation that kept me in the mode for continuous hard work,” Garba Lawal said.

“I followed his footsteps, admiring his style of play. He just could not stop scoring; as a striker, he knew where the goal was every time.”

How things ended so anticlimactically is difficult to understand, still. After scoring Nigeria’s first-ever World Cup goal and creating one of the competition’s iconic images, he would not score another in that tournament in the USA. Allegations of a squad gang-up against him, fuelled by jealousy, have raged in the decades since, and were given oxygen not just by comments from Sunday Oliseh, but by Yekini’s detachment and retreat into his own shell following that Mundial.

An unsatisfactory, unsalutary ending, then, but that’s life: it rarely offers conclusions as neat and decisive as Yekini’s goal were.

1. Stephen Keshi

Active years: 1979-1998

Honours: Côte d’Ivoire Premier Division x1, Belgian Pro League x2, Côte d’Ivoire Cup x1, Belgian Cup x2, Africa Cup of Nations x1

Ability: 8

Club career: 3

International career: 5

Social impact: 5

Leadership: 5

Total: 26

Stephen Keshi is, in all honesty, a little larger than life. He was so many things: a trailblazer, an inspiration, a bully, an icon, an organiser, a big brother. He is also one of the most gifted footballers to have ever played for Nigeria, a defender of significant prowess who was capable also of playing in defensive midfield, so good was he on the ball.

This latter point so often gets lost because of everything else. If Christian Chukwu established the captain archetype in Nigerian football on a national level, Keshi took it to staggering levels of influence. It was he who led the wave of professionalism in the country by signing for Ivorian side Stade d’Abidjan in 1985, presenting a whole new world of possibility to players on the domestic scene. His move to Belgian side Lokeren in 1986 led to a veritable tidal wave of Nigerian footballing talent crashing into Flemish country, and he played an ambassadorial role, helping them find their feet and navigate a tricky new environment.

His footprint was not limited to Nigeria, however. His guidance in the life and career of former prodigy Nii Odartey Lamptey led the ex Ghana international to refer to him as “father”. Former African Footballer of the Year Kalusha Bwalya called him a “leader” and said, “Stephen and I come from the same generation and we were pioneers of African players going to Belgium… in 1986 and there weren’t too many African players there. Stephen was a big man for Africa.”

It is no surprise then the esteem in which he was held on all fronts. He was so crucial to Anderlecht’s hopes that they refused to let Nigeria have him for the duration of the 1988 Africa Cup of Nations, instead flying him in and out of Morocco via private jet for only two matches in the tournament, one of which was the final. He was ‘The Big Boss’ not just in name, but in personality and importance.

He had the skill to back it up as well. On the ball, he was sublime, both in terms of distribution – he developed a knack for nonchalantly switching the play with the outside of his right boot – and carrying. According to veteran journalist Godwin Dudu-Orumen, Keshi was the most rounded defender Nigeria has ever produced: he “had the capacity to switch play from defensive positions into attack, and his transitional play was next to none.” It seemed he could activate it on command at times too: after he gave away the ball for Senegal to score at the 1992 AFCON, he simply sauntered upfield in the dying stages and spanked a left-footed finish into the top corner from the edge of the box to win the game and make amends.

Defensively, Keshi was deceptively pacey and a fierce competitor. “He was an astute football player, solid as a rock and was an imposing figure on the pitch,” Kalusha, with whom the Big Boss had many battles in Belgium, recalled. “On the pitch, he was something else and he didn’t make too many fouls, he was very clean. He used his strength well and was good in the air, he was quick, and he could build up from the back.”

A brash, occasionally overbearing man, Keshi was not universally liked. There have been suggestions of a hazing culture he may have fostered within the national team set-up, and allegations of undue influence over selections, especially while Clemens Westerhof was in charge. There is, without a doubt, some truth to the whispers, but what was clear was that the team always looked to him, and that he carried the burden of leadership extremely well, relishing it in fact. And if it was clear to him that it was in the team’s interest that he take a back seat – as in the final of the 1994 AFCON – he did not hesitate to do so. “Look, I'd love to play,” he explained to Westerhof of his decision to recuse himself from the tournament’s showpiece, “but this [is] a final.”

Delivering Nigeria’s second African title, as well as a place at the World Cup for the first time ever, count in Keshi’s favour, as does the fact that, in 1990, he became the first Nigerian to play in a UEFA club final. There were so many firsts with the Big Boss, so much so I feel fairly confident his standing as Nigeria’s greatest ever footballer is merited.