Just when you thought you were out, the Super Eagles pulled you back in.

It only took a win to overwrite all the negativity that had been etched onto the hearts of Nigeria fans, but it was not simply the case that any old win would have done. No, it needed to be the sort of win to reassert Nigeria as, once again, a competitive member of the continent’s elite.

In that sense, victory over the host nation was precisely what the doctor ordered.

Had the outcomes from the opening two matches been reversed (i.e. had Nigeria beaten Equatorial Guinea 1-0 and drawn with Cote d’Ivoire), the feeling would almost certainly have been a lot less exultant: context is everything.

The particulars of the performance did some heavy lifting as well. Jose Peseiro, derided for much of his tenure on account of his inflexibility and eschewing of balance, unfurled a largely untested scheme that worked not only in terms of the eventual outcome, but also in the sense that it got the team to buy in completely.

Only with total investment could a display of that level of discipline and controlled aggression have been achieved, and while the approach was hardly avant-garde, it played to the strengths of the personnel available for the most part. (It helped, too, that the Elephants were lumbering and, even when they stumbled upon an avenue worth exploiting, forgetful.)

As with much of the Nigerian experience, however, the wrong lessons are being learnt. Naturally, success against Cote d’Ivoire has been taken to be proof positive of the inherent superiority – within the context of the squad profiles available to Peseiro – of the back three/five, with some even willing to track all the way back to the Gernot Rohr era in search of confirmation to that effect.

However, the link between playing a back three/five and success is far from clean. In much the same way as some headline results have been achieved by resorting to that structure, there have been just as many – if not more – impressive outcomes from using the more conventional back four.

This is neither Football Manager nor Middle Earth—no One Ring rules them all. For the most part, the work of a coach is not, as some would like to imagine, alchemy; it is to, as much as possible, confine the weaknesses of their approach to the realm of the theoretical, while animating the strengths. This can be done with/by any structure, provided thought is applied to it.

In the case of Cote d’Ivoire, the strategic advantages of a back three/five were clear, and Jean-Louis Gasset’s side made it even easier to deploy against them by offering little variation on their attacking theme. What that does not necessarily mean is that the 3-4-3/5-4-1 structure is now a sacred amulet, an inviolable article of faith.

(If anyone is interested, here is a handy Twitter/X thread breaking down the tactical battle. I found it interesting)

Against Equatorial Guinea in the tournament opener, to hear Opta tell it, the Super Eagles mined 3.52 xG (and missed an eye-watering six big chances) and only gave up 0.26 xG while playing with a back four. There will be sterner examinations of Juan Micha’s side, but clearly Peseiro’s side is capable of remaining solid, while carrying a threat going forward. What’s more, his preferred vehicle for chance creation now appears obvious: bypassing midfield with direct passes into the final third and playing off the second ball.

It is fairly basic, and far removed from most people’s idea of “good football”. However, this squad does seem to have, within it, such a variety of profiles and abilities that even this most rudimentary of ideas can work. If this is indeed the express image of Peseiro’s dogma, then it may well be in Nigeria’s best interest to go game-by-game in terms of their structure, provided certain positional/territorial absolutes are fixed (having two inside forwards close to Victor Osimhen, for instance).

While that does not preclude a reprisal of three/five at the back from the Cote d’Ivoire win, it does mean that a ‘Christmas tree’ (4-3-2-1/4-5-1) is a real possibility as well. That would be a better, more interesting route than simply sticking stubbornly to the 3-4-3/5-4-1 structure.

Now, for a bit of a math spasm… Because a Nigeria tournament appearance would be incomplete without some arithmetic.

Going into the meeting with Guinea-Bissau, a place in the Round of 16 is, more or less, guaranteed. In a six-group, 24-team format, no team with four points has ever failed to progress from the Group Stage of a major international tournament. That tally will generally suffice.

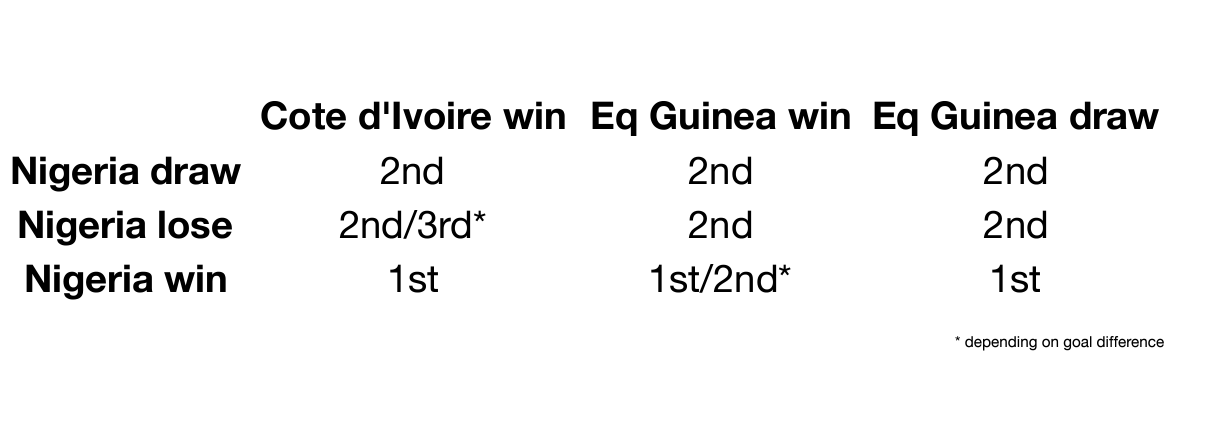

However, where in the group one finishes influences its path in the knockouts, and Nigeria could realistically finish in any of the top three positions in Group A. Here is a handy table of potential outcomes.

In only 33 percent of eventualities can Nigeria win the group A, and all of those involve the Super Eagles beating Guinea-Bissau on Monday. Eminently doable, of course, but should the wastefulness of the first two matches persist, then a second-place finish may well be the lot of Jose Peseiro’s side. Sidenote: only with one pair of outcomes is a third-place finish a possibility, and that would require a Nigeria loss.

So, what does the path to the final look like in the event of a first place finish? That would place Nigeria on the same side of the draw as Senegal and Mali (who, on balance, should be winning Groups C and E respectively), Egypt/Ghana, and probably Algeria as well.

Should Nigeria place second, they would wind up on the other half of the knockout stage draw. A Round of 16 tie with Guinea would almost certainly beckon, and elsewhere in that section would lurk surprise Group B winners Cape Verde, as well as Burkina Faso and pre-tournament favourites Morocco.

It’s always back-and-forth as our emotions are strongly linked with results.